LifeMap Solutions Teams Up with Mount Sinai on Digital Health

By Bio-IT World Staff

March 31, 2015 | This morning, LifeMap Solutions announced the launch of COPD Navigator, a digital health app for people living with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). The app is the second product to come out of LifeMap, which introduced Asthma Health earlier this month as one of the first class of apps built on Apple’s ResearchKit, a development platform for applications that capture patient-generated data for clinical trial-grade medical research.

Mobile health products that take advantage of smartphones as gateways to patients’ daily lives are a small but growing feature of American healthcare. Respiratory diseases like asthma and COPD are especially popular targets for these products, because management of these conditions often comes down to simple daily routines. Medication reminders and activity trackers, among the easier tools to implement in a smartphone app, make a useful foundation for controlling respiratory illness.

True to form, LifeMap’s COPD Navigator includes medication reminders, paired with a “gamification” feature that awards users points for sticking to their medication schedules. Those points can be redeemed for prizes made available by care providers who choose to offer COPD Navigator to their patients. LifeMap has also introduced a piece of custom digital health equipment to make its medication tracking more reliable. “We actually have a Bluetooth-enabled smart inhaler device that is entering a pilot program at Mount Sinai along with this COPD Navigator app,” LifeMap CEO Corey Bridges tells Bio-IT World. Attached to an ordinary inhaler, the device sends a signal to the user’s phone when maintenance doses are taken, allowing the app to keep a longitudinal record.

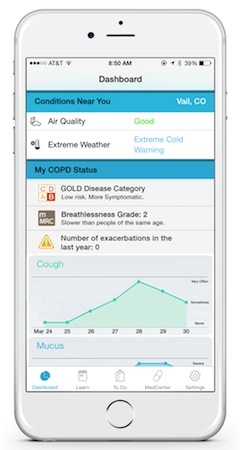

Built on Apple’s HealthKit, COPD Navigator also takes advantage of that platform’s steps-per-day function as a proxy for physical activity. A few additional features, like a weather and air quality tracker on the app’s dashboard and educational materials, try to account for the impact of respiratory disease on daily life, and to steer users away from exacerbating situations.

What Bridges hopes will set LifeMap Solutions apart from other early movers in mobile health, however, is its plan to quickly scale up, drawing on more complex biomedical features that can only be brought into the fold through close collaboration with care providers. LifeMap maintains two headquarters: one in Alameda, California, where the consumer-facing side of the company is at the fore, and a second nested within Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

“It’s no accident that our core partnership is with the Icahn Institute for Genomics and Multiscale Biology,” says Bridges. The Icahn Institute, a part of Mount Sinai, is best known for its systems biology approach to health, connecting clinical data with large-scale genomics and proteomics programs to interrogate the biological pathways of disease. Institute Director Eric Schadt is a major advocate of the view that bringing these disparate sources of data together can produce not only new treatments, but also more personalized ones.

Embedded in Care

LifeMap Solutions is a spinoff of LifeMap Sciences, a subsidiary of BioTime that creates tools for interpreting genetic data. (Bio-IT World covered the company’s quiet launch last year.) That background has informed the company’s perspective on the types of medical data that digital health platforms can take into account.

“In our very DNA, we’ve got a fairly visionary sense of what can be done at the cutting edge of life sciences,” says Bridges. “The genetic side of things is definitely something you’ll see more of in future apps.”

That doesn’t mean LifeMap’s apps will be linked to personal DNA sequencing programs in the immediate future, but the company’s platforms are built with the idea of eventually using genetic data and other biomarkers in mind. LifeMap’s long-term ambition is to link networks of apps like COPD Navigator to care providers’ electronic medical records, giving clinicians a glimpse into their patients’ daily activities while offering users themselves more personalized wellness programs based on data collected by research centers like the Icahn Institute. One hope is that this matrix of biological data and real-time activity tracking could one day predict specific health events, like exacerbations of symptoms that require immediate care.

The COPD Navigator Dashboard. Image credit: LifeMap Solutions

In the meantime, LifeMap’s partnership with Mount Sinai has opened up an unusually fine-grained ability to track patient outcomes. Teams in both the Mount Sinai-National Jewish Health Respiratory Institute and the Icahn Institute will draw on data from the first patients using COPD Navigator to understand how the app affects medication adherence and patient outcomes. The Icahn Institute will also test whether activity and inhaler usage data could be used to track the course of disease or predict specific flare-ups of respiratory symptoms. “It’s critically important for us to perform rigorous scientific analysis of how efficacious our mHealth solutions are,” says Bridges. “We’ll be running three different pilot programs with increasing populations, with increasing information tracked.”

Cooperating with caregivers at Mount Sinai has also informed the design of LifeMap’s clinician portal, which lets care teams monitor data from their patients with COPD Navigator or the Asthma Health app. “There have been mHealth and digital health products that have not taken input from care teams, have not taken into account doctors,” says Bridges. “That, and I’ll speak bluntly, is a huge mistake.” He adds that a particular request from clinicians was that the LifeMap portal not inundate doctors with extra work and non-actionable data.

As a result, LifeMap has created a sort of filter for the reams of information that COPD Navigator generates. Individual patients can go through whole weeks of data and see how their physical activity, or use of their rescue inhalers, has fluctuated — but their providers only see this data when it crosses some doctor-defined threshold that signals a worsening of symptoms.

New Models for Health

For now, tools like COPD Navigator are only available to small communities of users. Early adopters in the “quantified self” movement may proactively seek out digital tools to track the health patterns of their daily lives. For most people, however, these apps will only surface when care providers like Mount Sinai pilot disease-specific tools for particular groups of patients. The LifeMap Solutions apps, in their first iteration, are also limited to iPhone users, because they have been built on the Apple HealthKit and ResearchKit platforms.

Bridges, who was involved in the early growth of both Netscape and Netflix, believes that as smartphone technology continues to advance, and early test runs at hospitals get off the ground, digital health will follow the same trajectory as previous IT technologies.

“I think it’s definitely going more and more mainstream,” he says. “We have seen this type of situation play out before in different industries. Web browsers themselves started out as an early adopter trend, and then went mainstream.

“People are going to take an interest now in the specifics of their own health,” he adds. “We’re going to understand and manage our health in a much more personal, much more empowered way.”

That said, until data comes in from pilot programs like the one at Mount Sinai, it’s hard to predict what form the most successful digital health platforms will take. Simple apps that track steps-per-day and give weather updates might be helpful for narrow slices of the population, but their reach is likely to be limited. LifeMap’s more ambitious measures, to leverage the systems biology expertise of the Icahn Institute, will require a much deeper understanding of the diseases the company targets, and could also invite FDA scrutiny.

LifeMap’s current apps don’t diagnose of prognose disease, says Bridges, but as their capabilities grow, they may become subject to new regulatory pressures and higher bars for performance. “Over the next couple of years there will be occasional surprises and adjustments,” he says, “just as we’ve seen in other industries that have been positively disrupted by technology.”

Still, the potential rewards are great, given both the country’s renewed focus on personalized medicine, and the unprecedented computing power available in patients’ pockets. Academic medical centers like Mount Sinai are eager to tap into new lines of communication with their patients, and Bridges wants to be in on the ground floor when they do.